I want to preface that a lot of the issues I run into below are because of my own ignorance around the tooling, and a lot of the detail I include is to show what that ignorance looks like, since many people reading this might be used to Fabric or at least data engineering.

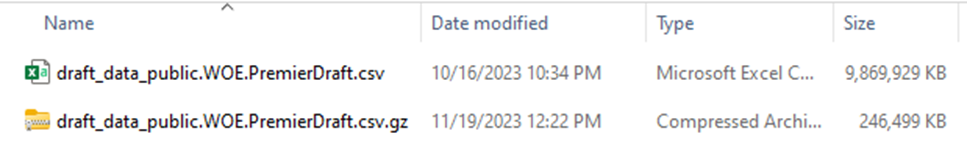

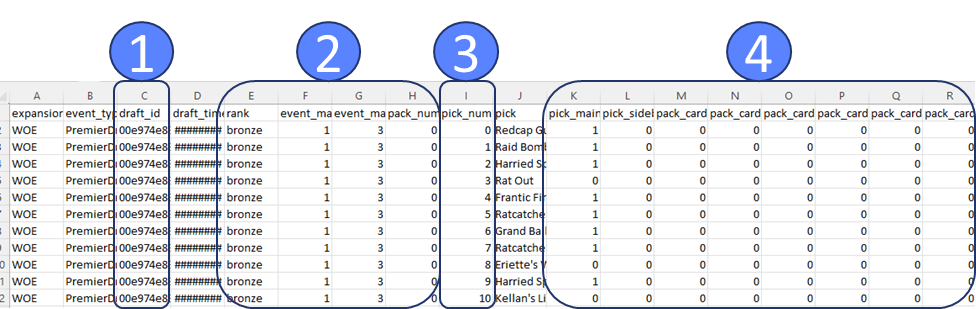

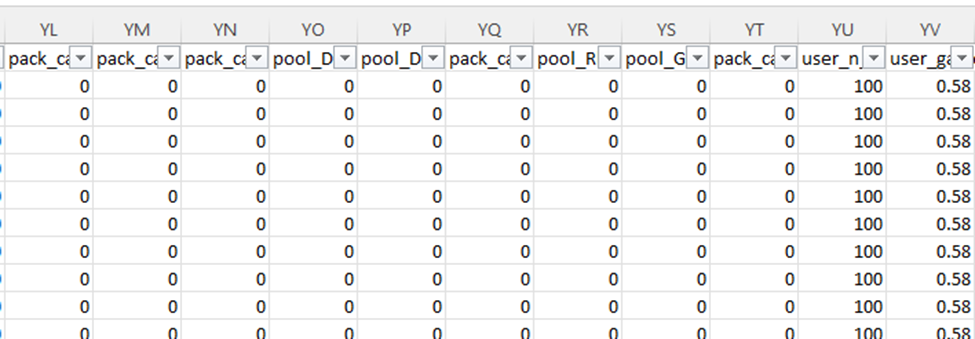

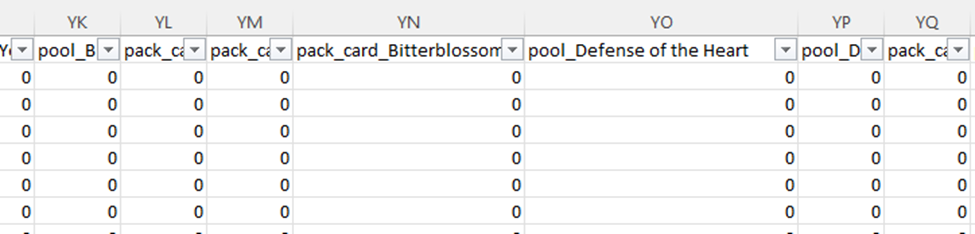

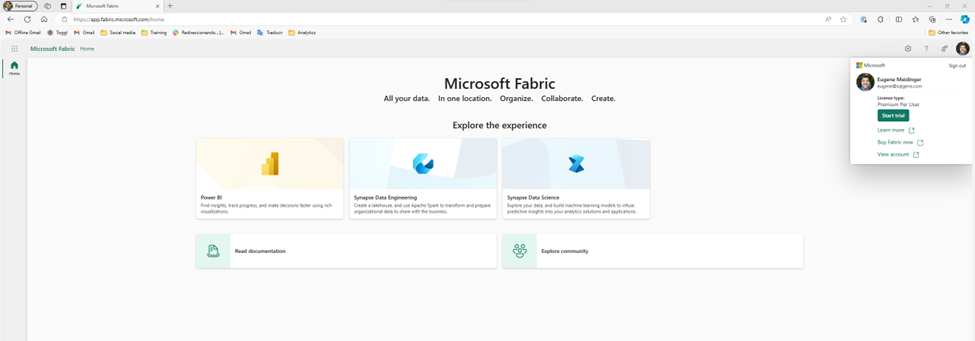

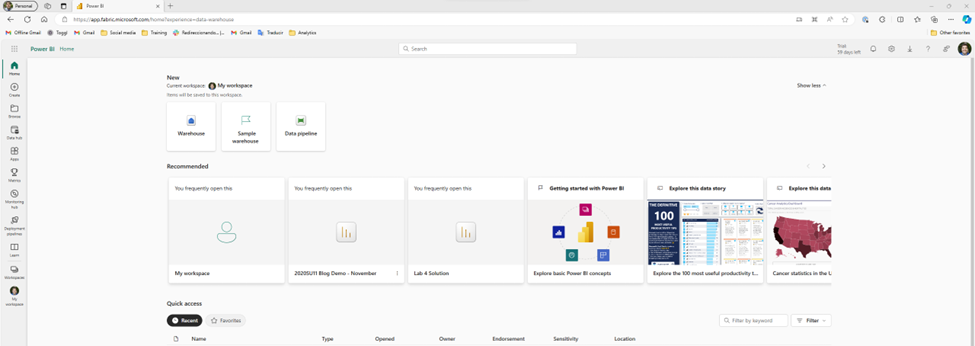

So, last week we took a look at the data and saw that it was suitable for learning fabric. The next step is to upload it. Before we do anything else, we need to start a Fabric Trial. The process is very easy, although part of me would have expected it to show up on the main page and not just in the account menu. That said, I think the process is identical for Power BI.

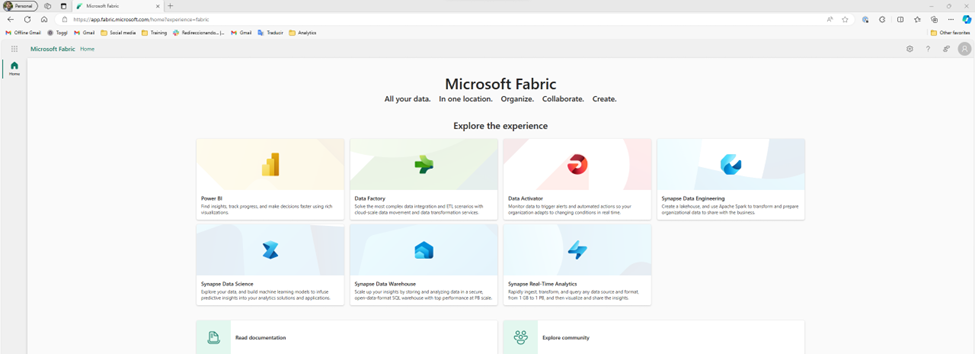

Once I start the trial, more options show up on the main page. Fabric is really a collection of tools. I like that there are clear links at the bottom for the documentation and the community.

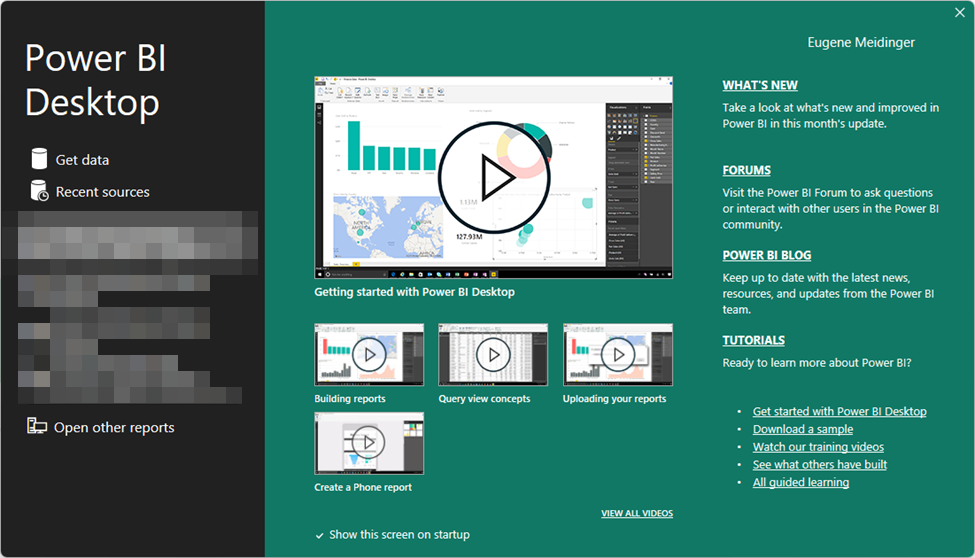

I think something that could be clearer is that the documentation includes tutorials and learning paths. While I understand that the docs.microsoft.com subdomain has been merged into the learn.microsoft.com subdomain, when I see “Read documentation” I assume that means stuffy reference material as opposed to anything hands on. This is an opportunity to take a lesson from Power BI Desktop by maybe having an introduction video, or at least having a “If you don’t know where to start, start here” link.

Ignoring all of that, the first I’m tempted to do is select one of these personas and see if I can upload my data. So, I take a guess and try Data Warehouse. Unfortunately, it turns out that this is more a targeted subset of the functionality. Essentially, as far as I would be aware, I’m still in Power BI. This risks a little bit of confusion, because the first 3 personas (Power BI, Data Factory, and Data Activator) are product names, so I’m likely to assume that the rest of them are also separate products. In part, because that’s how it historically has felt to me in Azure, as I’ve talked about when first learning Synapse.

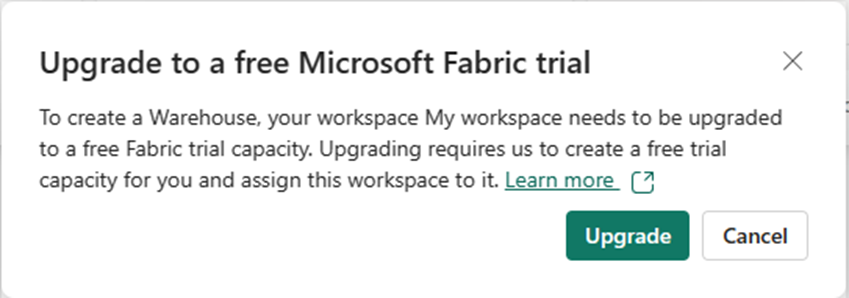

Now thankfully, I’m aware that the goal of Fabric is to have more of a Power BI style experience, so I’m able to quickly orient myself and realize it is showing me a subset of functionality instead of a singular tool. I also see “?experience=data-warehouse” in the URL which is also a hint. So, I go ahead and click on the warehouse button, hoping this is what I need to upload my data. Unfortunately, I get a warning.

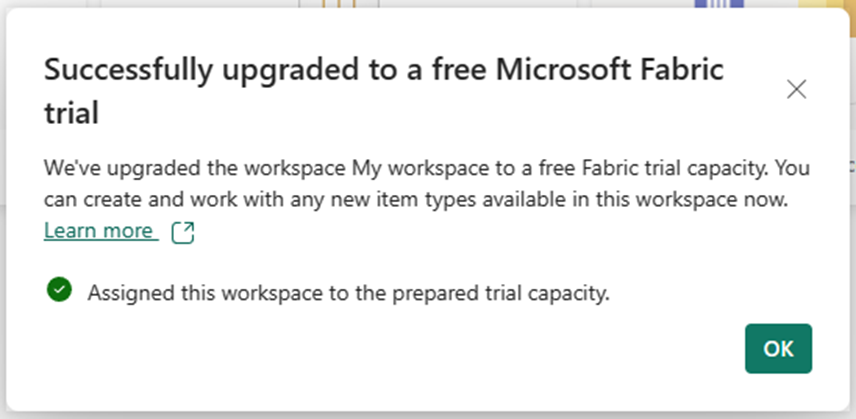

The warning says I need to upgrade to a free trial. But I just signed up for the free trial! Reading the description, I realize that I need to assign my personal workspace to the premium capacity provided by the free trial. This is a little confusing, and at first I had assumed I ran into a bug. I click upgrade and it works.

Finding where to put the data

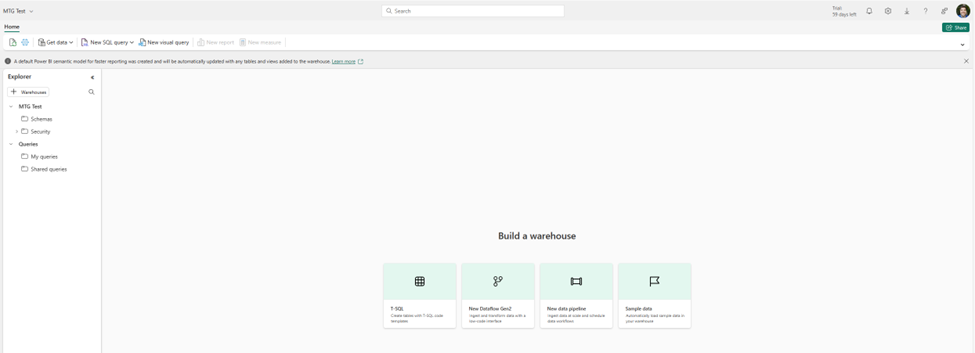

Next it asks me for the name of my warehouse. I choose “MTG Test” and cross my fingers. Overall it seems to work. Again, I’m presented with some default buttons in the middle. I see options for dataflows and pipelines, and I assume those are intended for pulling data from an existing source, not uploading data. I also see an option for sample data, which I really appreciate for ease of learning.

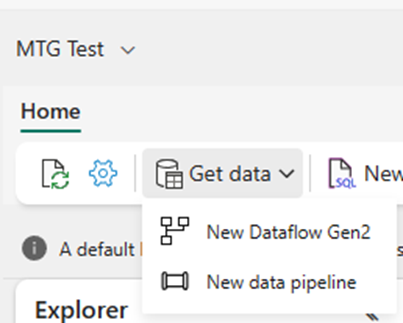

I see Get Data in the top left, which I find comforting because it looks a lot like Get Data for Power BI, so let’s take a look. Unfortunately, it’s the same 2 buttons. So, we are at a bit of an impasse.

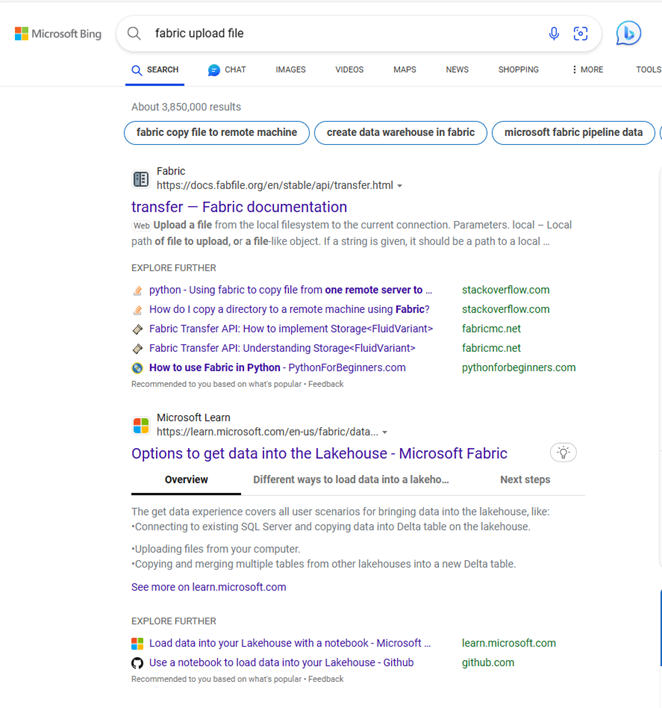

I click on the dataflow piece, but I’m starting to feel out of my depth. If my data already existed somewhere, I’d be fine, but it doesn’t. I have to figure out how to get the data into the data lake. So I back up a bit and then Bing “Fabric file upload”. The second option is documentation on “Options to get data into the Fabric Lakehouse”.

The first option shows how to do it in the lakehouse explorer. I go back to my warehouse explorer, looking for the tables folder, but it’s not there. I see a schemas folder, which I assume is maybe a rename like how they recently renamed datasets to semantic models. I assume that maybe schemas are different than tables and that I need to find a more detailed article on Lakehouse Explorer. It probably takes me a full minute to realize that a warehouse and a lakehouse are not the same thing, and that I’m probably in a different tool.

So, I backup again and search for the more specific query “fabric warehouse upload”. I see an article called “Tutorial: Ingest data into a Warehouse in Microsoft Fabric”. I quickly scan the article and see it suggesting using a pipeline to pull in data from blob storage. So I know that’s an option, but I’m under the vague impression that there should be a way to upload the data directly in the explorer.

Giving up and trying again

I dig around in Bing some more and I find another article called “Bring your data to OneLake with Lakehouse”. From demos I’ve seen of OneLake, it’s supposed to work kinda like One Drive. At this point I know I’m misunderstanding something about the distinction between a warehouse and a lakehouse, but I decide to just give up and try to upload data to a lakehouse. The naming requirements are more strict so I make MTG_Test.

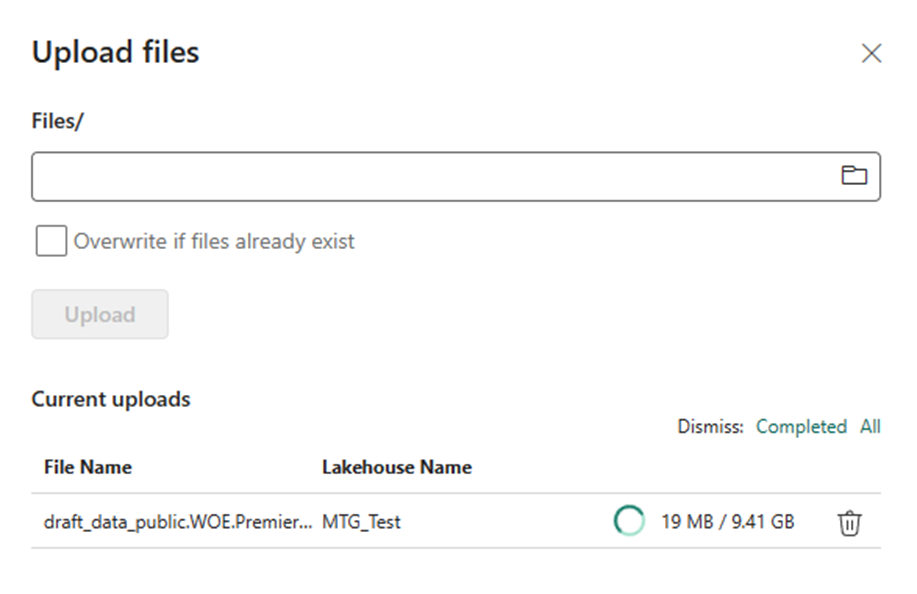

I got to get data, I see the option to upload files. I upload a 10 gigabyte file and it works! Next week I’ll figure out how to do something with it.

Summary

Setting up the fabric trial was extremely easy and well documented. As far as I can tell, there’s a lot of getting started documentation for Fabric, but I wish it was surfaced or advertised a bit better. I run into a lot of frustration trying to just upload a file, in part because I don’t have a good understanding of the architecture and because my use case is a bit odd.

Overall, I’m feeling a bit disheartened, but I have to remind myself that I ran into a lot of the same frustrations learning Power BI. Some of that was the newness, some of that is learning anything, and some of that I expect the product team will smooth out over time.

I also acknowledge that I’d probably have an easier time if I just sat down and went through the learning paths and the tutorials. In practice though, a lot of times when I’m learning a new technology I like to see how quickly I can get my hands dirty, and then back up as necessary.