Back in December, I wrote about all of the hard lessons I was learning by working for myself. Three months later, many of those challenges have shifted, which warrants a new blog post on the subject. In general, I’ll try not to repeat points from the last post.

So let’s assume that you’ve been working for yourself for 6 months. It’s at this point that one of three things has occurred. 1) You’ve burned up all of your savings and need to go back to a normal job, 2) you are getting enough work to make this sustainable, or 3) you are muddling your way through, making enough to pay the bills, but not enough to be happy.

If you have burned all of your savings it is painful, but you learned something valuable and have clear next steps, i.e. get a job. Consider this like a European gap year. Now you know this isn’t for you.

The barely sustainable path is more dangerous because you might shamble along for 5 years, unhappy and not growing, but too scared to give up your dream. Now is the time to make that hard choice. Step it up or quit. Don’t wait until 60 months in to decide.

Let’s assume instead that you are doing well, really well. Perhaps too well, even. If you are getting plenty of work, then there are new and very important questions to answer. How do you define work and how do you manage it? How do you decide to “release” work into your enterprise? When do you say no?

If you cannot define, manage and prioritize work within your one-person organization, you will overcommit, incorrectly prioritize and eventually fail. It is as simple as that. I have been eating a lot of humble pie this month as I’ve had to delay or cancel projects. This is because I planned poorly and overcommitted.

What is different?

So how is work any different than a normal job, and why do we need a better handle on it? So the very first thing is that in a regular job, the work is often more consistent or steady-state. In most cases, the variation in requests each week isn’t huge and so you can predict your overall workload. That workload may be more than you can handle, but you can still predict it.

Spikey workloads

Freelance work, in contrast, is extremely spikey. It’s often called “feast or famine”. There are a number of reasons for this. One is that often you’ll land a big project and the customer wants you to work on it RIGHT NOW. I’m wrapping up a 120 hour Power BI project, and the customer’s ideal would have been for me to complete it all in three weeks. My ideal would be to spread it over 12 weeks. The reality lands somewhere in the middle.

Another reason the work is so spikey is the very long lead times on the sales cycle. Some projects can take 3-6 months from first conversation to the contract being signed. By the time the sale closes, you may have already signed up for other commitments. Even worse, guess when you will have the most time to focus on sales? When your funnel is empty. So you get this ugly sine wave of working a ton on sales, then landing a bunch of work and being too busy to work on sales. Then the cycle repeats.

One other reason for the spikiness is if you are a freelancer, you are likely working alone at first. Which means you can’t take emergency work or that 120 hour project and spread it around as easily.

You control your workload

At my last job, I had very little control over what work got “released” or “approved”. I could prioritize and order my tasks, but I wasn’t the one coming up with them. The bulk of my work was based on requests from customers either internal (co-workers) or external.

As a freelancer, you have the power of saying no. You can fire customers. You may not be in a financial position to do it just yet, but that is one of the goals. Paul Jarvis describes it as being able to have a diva list. You control the conditions of your work.

This is especially true when it comes to non-billable work.Nobody wants to turn away paid work, but it’s totally on you if you decide to sign up to write a book, or start blogging every week, or present to more user groups. And because your workload is so spikey, you may sign up for these things when your workload is in a trough and regret it when work picks up. Which is…exactly the trap I fell into.

Your work is less visible

If I present at a user group, is that work? If I chat with people on Twitter, is that work? If I read a book about marketing, is that work? The answer to all of those is a distinct maybe, it depends. If they are work, then they take up time and they need to be monitored. Otherwise you’ll end up wondering why you aren’t spending more time on paid work.

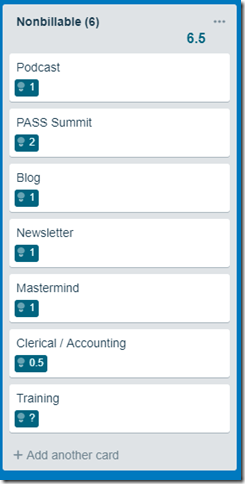

One of the “click” moments for me was when I mapped out all of my non-billable commitments I had made. On an ideal week, I am spending a FULL DAY of work on things that don’t get me paid. Well, at least not directly. Secretly I hope that you’ll start reading my newsletter, fall in love with me, and watch my paid Pluralsight courses.

This was not a problem at my last job, because I had a standard set of hours that I worked, and when I went home it was my time. Anything I did extra, like blogging, was icing on the cake. Now it’s a lot blurrier. I treat things like blogging or my newsletter as marketing expenses. I consider those things to be “work” and I track my time in Toggl accordingly.

Which reminds me! Are you tracking your time? If not start now. Toggl.com is completely free and has a simple app too. We manage what we measure. Nobody says you have to work 40 hours per week, but you need to make your work visible to you so that it can be managed and controlled.

What can we do?

So, I’ve been wrestling with these issues a lot. Going freelance reminds me of the Foundation series by Isaac Asimov, where a society faces a life threatening crisis, resolves it and then faces a completely different crisis. Managing work is my current crisis. There are two books that I can recommend that have been foundational (no pun intended) for how I relate to work.

Getting Things Done

The first book, which has transformed my work for the past 8 years, is Getting Things Done by David Allen. There is a lot to this book, but it’s all quite practical stuff. It’s the sort of thing that you’ could have invented yourself with enough time and effort. One of the key insights is that David breaks work into 3 main buckets:

- Pre-defined work

- Work as it appears

- Defining your work

Realizing that it’s valuable to spend time predefining your work, giving it a shape, and making it actionable, these are all amazing insights. GTD helps us turn a nebulous cloud of “work” into manageable, actionable tasks.

What is does not do, however, is provide a lot of guidance on managing the capacity, flow and priorities of our work. While it touches on looking at higher level goals, it treats work as a giant refined todo list, filtered by specific contexts. There is nothing in it that says “Hey, maybe don’t sign up to write a book because you might get busy.” For that, our next book comes in to play.

The Phoenix Project

Until very recently, I have never understood Devops. I got the general idea of unit testing, CI/CD and so on. But I never grokked Devops, to understand it in my bones. The Phoenix Project changed all of that , and it changed how I relate to work. Minor spoilers ahead.

In The Phoenix Project, work is defined in 4 different buckets:

- Business projects. Projects that add value to the bottom line.

- Internal projects. Projects that improve stability and efficiency.

- Changes. Sources of risk introduced by the two above.

- Unplanned work. Break/fix type work.

This ties in to the idea of the billable/nonbillable distinction I spoke about easier, as well as making work visible. As a freelancer, you are a “factory” of one, and you have to understand what commitments, internal and external, that you’ve taken on.

After reading the book, I felt utterly embarrassed, like some plant manager who was drunk on the job releasing work willy-nilly. What I learned from this book is that work in progress is the silent killer of productivity and I was producing tons of it.

Another insight from the book is to ask what are your work centers, a la the theory of constraints. What constrains the types of work you can do and when? In GTD, those constraints are largely physical and contextual: phone, email, computer, office, etc.

But in applying the theory to my own life, I realized a lot of my constraints are brain power and energy. Often I was doing brain-less work, like my newsletter when I was at peak energy, instead of doing my more intensive work, like writing courses. It was revelatory to see the constraints and “work centers” in my own factory of one.

One of the steps that I took to address this was to start capacity planning. I looked at my hours in Toggl, and looked at how much of that time was billable. Then I mapped out the total hours for my current commitments, then divided by the previous number. This helped me assess how many weeks of backlog I had at the time.

Summary

As a freelancer, you have much more control over what work you do or don’t do. But, the definitions for what counts as work get hazier and less visible. You need to take time to resolve that fact, as well as looking at your capacity in whole and over the long term.

I personally still haven’t gotten the hang of this. I look forward to your thoughts and book recommendations in the comments below.