There’s some valuable discussion going on regarding diversity and conferences. I wrote about it last year. I’d like to write more of my thoughts on the subject, but so far I’ve been overwhelmed with my day job and I have some older posts I owe people. That said, I figured this would be a quick way to add some context and something useful to the dialogue.

Below is a blog post I wrote in July 2019 in response to some frustration to the selection process that year. For each section, I’ve added a “What this really meant” section to add some background context. I hope this makes some of the conversations more fruitful.

A peek inside the program selection process

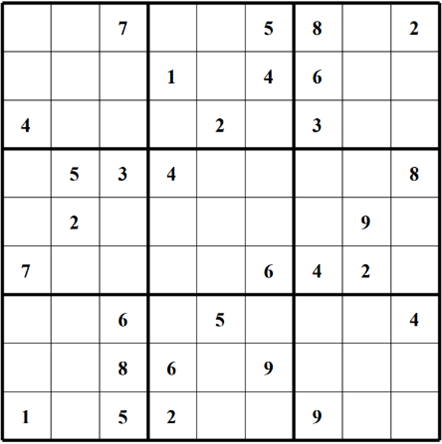

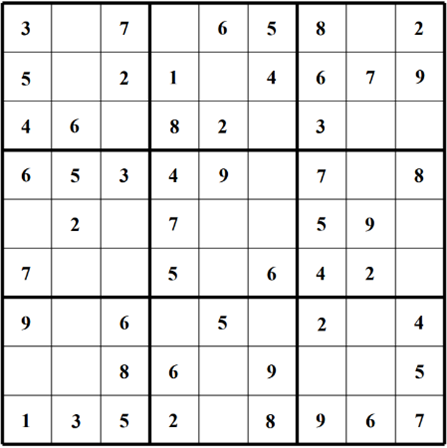

As one of the program managers for PASS Summit, I always wish that people knew more about all of the steps involved in selecting the community sessions each year. The difficulty of balancing all of the tradeoffs and constraints is an incredibly challenging and rewarding task. I personally like to think of it as a high stakes game of Sudoku, and in fact I will be using that analogy to help explain the process.

In this blog post, we will take a high-level look at the different stages of the PASS Summit selection process, as well as a few of the factors that we try to balance as a team.

What this really meant

Back in March of that same year, there was some particular controversy. I forget the exact details, but I recall writing a long Twitter thread about “hey we are human beings, not some shadowy cabal.” Given the regular lack of transparency about the the selection process in general, any conclusions people jumped to were entirely understandable. My hope was to help change that as much as I was able to.

Simply put, if you don’t communicate your process, people will assume the worst.

As a team, we had hoped that each one of us could write a blog post about the process and perhaps give some better insight and transparency. Unfortunately being a program manager was essentially a 50-75 hour per year commitment, where the only financial compensation was entry to conference and maybe some speaker swag. It was difficult to make the time for going beyond that task.

A year later, in the dying days of PASS, I wrote about the difficulties about improving transparency. I think the organization had gotten into a bit of a doom loop, but it’s questionable how much of a difference I could have made alone. Many of the issues stemmed from decisions outside of my control.

Overall Timeline

The very first step is when the PASS Board sets the overall strategic vision, which we, as the program team, then work within. This year, for example, we saw the introduction of the architecture, data management, and analytics streams. One top of that, the spotlight topics for 2019 are Security, AI, and Cloud – which means we need to make sure those topics are well-represented in each stream. So, before we even begin, we already have two constraints to consider in our game of Sudoku.

Next, call for speakers opens up. Without our speakers, we wouldn’t have a conference, full stop. I especially appreciate all of the new speakers who have submitted. I know, for me personally, it was an emotional rollercoaster when I submitted back in 2016 and 2017. I would worry, for a long time, about getting selected or not and then be a nervous wreck if I did get selected!

Once the call for speakers closes, the abstracts need to be reviewed. Each year, we select about 20 volunteers to join the program committee. This team does the bulk of the work, spending hundreds of hours reviewing hundreds of abstracts, over 6-8 weeks. We simply could not get through the hundreds of sessions each year without the help of all of these volunteers.

Once all the abstracts have been reviewed, the program management team drafts the initial community line-up. The program management team consists of 4 volunteers, myself included. We take all the feedback from the program committee and align it to the vision and direction from the PASS Board in order to draft the initial lineup. This combines the community sessions with any targeted sessions that have already been published. Oh, and did I forget to mention that while this process is happening, the PASS Board educational content group works with us and PASS HQ to target initial waves of content? This is based on industry trends, thought leader feedback, session evaluations, and so much more! Just one more set of constraints to add to the board

Next, we reach out to community thought leaders and the PASS Board for ongoing feedback and gap analysis. Thought leaders are a wide-range of people from the community and industry that we reach out to get their perspectives on key topics, trends, and gaps they see in educational offerings. There are a lot of cooks in this kitchen to help make sure we don’t miss anything. The community program is then completed by the program management team with final approval from the PASS Board educational content working group. Overall, this portion takes just over a month, with the community lineup announced in early-mid July, and any final sessions announced in August. In the next section, we will go into detail regarding the selection process.

What this really meant

What I wanted to communicate with all of this is that the process was complicated. We often would have high level scheduling constraints set by some combination of the board and C&C. This generally came in the form of high level themes or content goals, such as learning paths. There were a lot of constraints being added and sometimes we didn’t have as much time available as other years. When we had less time, we screwed things up and made mistakes.

A recurring theme as well was that we needed outside opinions to avoid screwing up. A lot of the balancing process was a series of spot checks, and it was easy to forget one. It was also easy to lose touch with the community and how they might respond. We knew our process, we knew the challenges we were facing, and we knew we had good motivations. It was very easy to lose touch with how others might interpret things. It was easy to forget what it was like to be a speaker, nervously hoping to get in.

Selection process

Whenever you play a game of Sudoku, there are very few numbers on the board, so almost any choice you make will fit within the existing constraints.

The same flexibility applies with choosing sessions. Some of the session slots are already filled with invited speakers, but generally we have a lot of flexibility at this stage. So, the first thing we do is take all of the sessions and sort them by their abstract review score. The idea is to start with the highest quality sessions and have the cream rise to the top.

Once we start filling in the slots, however, we then need to consider a number of factors. This is like being near the end of a game of Sudoku, it gets harder and harder to meet all of the constraints and this is where the game, and our job, gets really tricky.

Here are just a few specific examples of factors we review:

- Strategic vision

- Content areas

- Topic depth/level

- Sessions by audience

- Speaker performance

- Speaker diversity

The first thing we have to consider is how do our sessions balance in terms of content and level. Do we have 15 sessions on Power BI but nothing on SSIS? If we look at the line up by individual audiences are we serving everyone? Do we have any gaps? How much 400/500 level content do we have? Whenever we survey our members, they consistently request in-depth content, but for 2019, only 0.5% of the submitted sessions were at the 500 level. This can present challenges for us.

I could go on and on about all the factors we consider, but I hope that this gives you better insight into the selection process.

The sessions have now been announced, and it is a great feeling to see it all come together. I look forward to seeing all of you at PASS Summit in the fall.

What this really meant

What I really hoped to communicate was that we were juggling a large number of constraints, and the more that got added or the less time and resources we had, the more likely we would fail one of those constraints.

I also was happy to mention diversity as a consideration. I would have loved to have go into more detail at the time, but there was a worry that it was a sensitive subject and that being honest about it might cause controversy. So it was resigned to a bullet point at the end of the list.

Diversity for us was a regular spot check for us. While the main goal was to produce a schedule that would sell well and that people would like to attend, we knew very well that we had to work towards diversity. It would have been easy to just selected the most well known speakers or just selected the best sounding abstracts, but this would have created a schedule that wasn’t reflective our speaker pool and definitely not reflective of the average IT worker.

We knew for a fact that if we let an all male panel slip through, we would get roasted, and rightfully so. We knew that the televised sessions and precons put a spotlight on the speakers, and if we ended up with line up full of white guys like myself, that was a failure.

One final thing, I want to acknowledge that conferences today have a harder time than we did. It was easier when we have lots and lots of submissions both for precons and general sessions. I fully believe that post pandemic, conferences are likely starting with much less diverse of a speaker pool.

Being a program manager in 2022 is a difficult job. But just like how expectations for speaker compensation are rising, so are expectations for a diverse schedule. Ultimately more resources have to be allocated to the task as it gets more difficult.